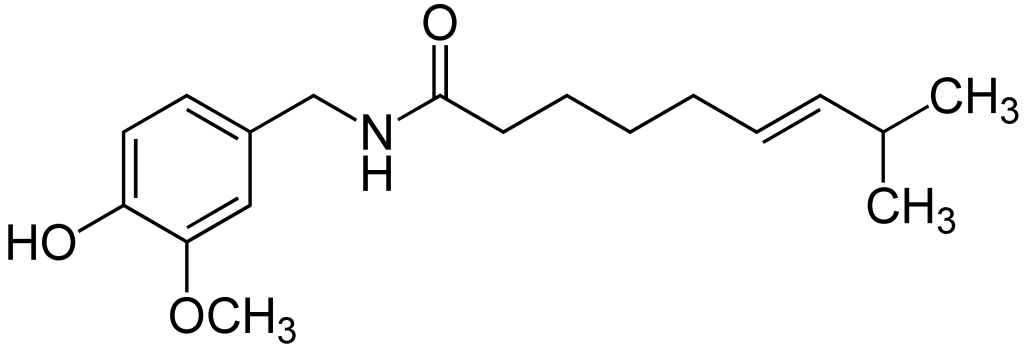

Over 200 years ago, a chemist named Christian Friedrich Bucholz succeeded in isolating capsaicin. Pronounced cap-SAY-sin, it is the source of heat in your chilies. Since then chemists have figured out how to extract near 100% pure capsaicin extract from peppers. In 1930, chemists reported the first synthesis of the stuff. (Synthesis is the fancy term for replicating the chemical compound capsaicin without the need to grow peppers.) Today capsaicin is widely used in medications, pepper spray, rodent repellents and more. As I explained in an earlier post, we use the Scoville scale to measure the heat of peppers.

Why do chilies produce capsaicin in the first place? Well, scientists have observed some pretty clear benefits of being ‘hot’. First, they discovered capsaicin is irritating to mammals but not to birds. In the wild, birds help spread seeds around which is good for the chili plant. They tend not to crack small seeds open, so wherever they roost, the birds plant chili seeds at the same time. On the other hand rodents tend to chew up seeds, so they’re not going to sprout – bad for the chili plant.

I can personally attest to the effectiveness of hot peppers in repelling squirrels. We’ve tried many repellents in the past with limited success. However, last fall after planting a batch of spring bulbs, Tony spread my pepper sauce mash on the garden (mash is a by-product of fermented hot sauce making) . While the heat doesn’t hurt those fluffy tailed rats it sure ruined their appetite for our tulip bulbs!

The second benefit of capsaicin is due to it’s effect on a common fungus in chili plants – fusarium. That’s the same family of fungus that causes your tomato leaves to wilt in humid weather. Fusarium is quite common in soil and attacks many types of plant – in peppers, it is damaging to the seeds. It turns out that capsaicin limits the growth of the fungus which get inside the fruit when pests burrow through the pepper wall.

The hottest part of the pepper is the placenta. Yes, peppers have a placenta too! It’s the light coloured pithy tissue where the seeds are attached inside the hollow pepper fruit. The seeds get all their nutrients through the placenta. You’ll often read advice to discard the seeds if you want less heat – well it’s actually the white bit that has the highest heat. The seeds are hot too, but not to the same degree.

Capsaicin is good for pepper plants – but is it good for people too?

It turns out capsaicin has many benefits to humans. The chili pepper spread rapidly around the globe after it was first retrieved from the New World by Columbus. It’s no coincidence that hot countries quickly adopted them into their cuisine because capsaicin helps prevent food from spoiling. It has both anti-bacterial and anti-fungal effects and, of course, they taste really good too. In times before refrigeration, this was a valuable property.

Another myth buster – hot peppers are good for digestion! It’s a common misconception that spicy food causes heartburn and stomach trouble, but in fact it’s the opposite. Capsaicin stimulates the production of saliva and gastric juices that improve your digestive performance. For those on a low FODMAP diet for IBS, chili peppers are just fine in moderate quantities. While many people (and physicians) believe spicy food is bad, I suspect it’s because those dishes often include lots of onion and garlic – 2 of the primary foods to be avoided on a FODMAP diet.

While capsaicin is the main source of heat, there are a handful of other, related compounds called capsaicinoids that also affect the chili burn. Because different types of chilies have varying levels of these compounds, humans have a range of reactions. Depending on the capsaicinoid mix, you might experience a delayed or immediate reaction, a brief burn or a lingering one, etc.

Fortunately, the heat we humans sense from capsaicin is a kind of false alarm. Capsaicin triggers receptors on your tongue that normally fire only with high temperatures or acid. However, the chili burn is harmless. Furthermore, after you eat a bit, you develop a tolerance for it and subsequent bites don’t have the same fire in them. Eat up and enjoy!

Sources and further reading

Smithsonian Magazine, What’s So Hot About Chili Peppers?, April 2009

Harvard University: Science in the News Blog, The Complicated Evolutionary History of Spicy Chili Peppers, Nov 2012

National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), Harnessing the Therapeutic Potential of Capsaicin and Its Analogues in Pain and Other Diseases, July 2016

draxe.com, Cayenne Pepper Benefits Your Gut, Heart & Beyond , May 2018

bbc.com, How spicy flavours trick your tongue, January 2015